"...government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

- Abraham Lincoln, November 19, 1863, Gettysburg Address

Breaking down Governance

Hello! Welcome back. In this page, we will discuss a basic concept, which is an example of one of those basic concepts we talked about in the post where we discussed how to easily break down examples in A Levels for better results. If you haven’t read that post, do go read it first and come back to this. (Don’t worry! It’s a quick read.) Otherwise, please feel free to access our other free GP notes!

Today, we will discuss the topic of governance in the context of General Paper or even English! Of course, just to be clear, while this is primarily targeted towards GP, what we’re about to expound on can also be used to understand some topics in H2 History. We’ll touch more on it as we move along.

This is a basic breakdown meant for students aged 15-18 years old in Singapore. If you’d like more deep-dive things, I’d urge you to go and watch more in-depth videos by many of the wonderful content creators out there, or better yet, read more books on governance! (Something like Baron Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws)

Or, hey, if you feel that this page is too long, feel free to watch this YouTube Video on the left!

(It’s the same word-for-word content)

So, back to it. Now, in General Paper, governance is one of the most important topics. There are two reasons for this:

1. The first is due to the fundamental nature of this institution and how it affects the lives of the masses;

2. Practically speaking, it’s one of the topics that would often come out for your A Levels, be it as a topic on its own OR as an ancillary topic of discussion when discussing other topics.

That said, governance can certainly be a very complicated topic. However, it can be broken down into chunks such that we can better understand it, so let’s demystify it!

So… what is Governance?

There are four things in increasing levels of complexity that we need to understand about governance: what is it, why it is done (purpose), how it’s done (civics), why things go wrong. In secondary levels of education – specifically, in the context of the subject of Social Studies – you’d learn about the first two things albeit with a rudimentary understanding.

For the subject of General Paper, however, we should already be earnestly dealing with how it is done and why things go wrong. So, let’s first begin with some simple definitions.

Learn more: Singapore secondary school Full Subject-Based Banding Syllabus

Learn more: Singapore A Levels Syllabus

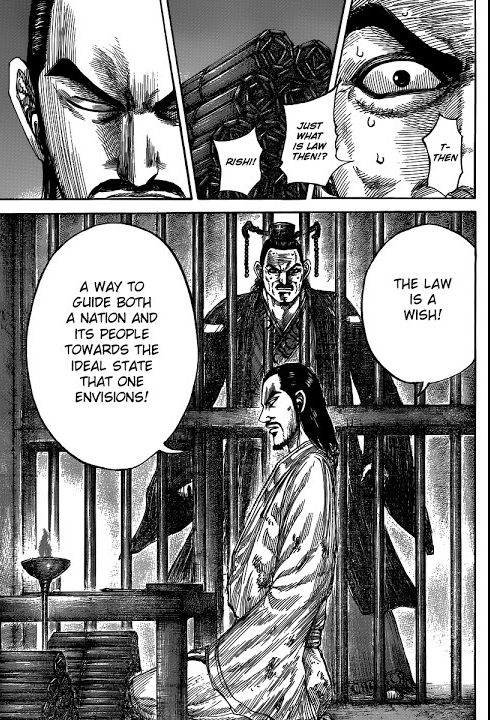

So, what is governance exactly? In short, it is the act of governing. This means an entire institution or organisation, filled with leaders and administrators, carrying out the act of running a nation’s day to day operations. How they typically do this is through implementing or enforcing laws, policies and regulations. These are actions that the government takes, or, to quote Rishi from the manga Kingdom, wishes by the government in terms of how they want their people to lead their lives. There can be direct or indirect influences on society, but it really depends on the context.

Now, what this dependence on context means is that you can explore what is governance in different situations. This can be in terms of economics, law and order, social affairs, education, defense, etc. Of course, often, these laws and policies work together to create a cohesive whole.

So, for example, in economics, the Singaporean government often tries to maintain a budget surplus, which means that government earnings would outstrip spending. This is part of a longer term strategy, one of maintaining fiscal sustainability to prevent (as much as possible) debts, or to protect against a rainy day, like the COVID-19 crisis. In education, we strive to push students to institutions of higher learning – not just to maximise human development – but also to capitalise on our only natural resource, which is human resources. Policies thus consider many other factors and contexts.

At this juncture, to prove this entire talking point, just go with any examples of policies implemented by a government like the one on Singapore’s approach to its budget. Whether or not your examples reflect virtuous policies in line with its purpose… that’s another question to deal with another time.

What is governance and what is its purpose?

So, with that in mind, what is the government’s purpose? Well, in a phrase, it is to ensure the welfare of the people. This means fulfilling the long and short term needs and interests of the people. If there’re extra resources, yes, they can give the people what they want, but a responsible government would always prioritise the former. As a result, fundamentally, in our basic analyses, this becomes our starting off point upon which we can build further analyses, which is that a government would seek to secure said welfare interests. For instance, this means that in education, they should seek to create a robust public education system that is affordable and accessible while fulfilling, in short, a basic human right.

Some good examples include the Scandinavian system and yes, the SG system. In social affairs, this means protecting minority interests, helping the poor, helping the disenfranchised and the disadvantaged. Any examples that demonstrate a government doing things to uplift the people tangibly would prove this point here. A basic example you can use in your A Levels GP essays can be social services present in nations like France, which has a comprehensive social security system aimed at supporting a large variety of things like healthcare, housing, workers’ benefits, etc., etc. If you are looking for a quick explanation for how it works, check out this video by the social security administration:

Now, of course, to train your critical thinking skills, what we can ask ourselves is this: why does it fall to the government to do this? This is where we need to first understand how the government derives its purpose in our understanding of what is governance.

What is governance: How governments derive their purpose

In order to better tease out the responsibilities and obligations of a government, we need to understand how it works. Thus far, we have explored the basic, fundamental purpose, but not its mechanisms and what such mechanisms actually represent.

The reason why it falls to a government to deal with such large scale societal problems is because it is the institution in society that SHOULD have the most influence and as a result, it should have the most resources and its actions would have the biggest impact on society.

An understanding of civics is important, because we may wonder: how does a government have the most influence? In general, in modern contexts, there are two ways a government derives its influence and therefore its power and resources: either they receive the mandate from the people, or they force the people into subservience.

Sharper students at this juncture would realise that we are, indeed, talking about political structures. When people give a government the mandate, it means that they give a particular government the authority to do something. How this occurs is typically through elections; people vote for their leaders and as such give them said authority. In such cases, it’s a democracy.

On the other hand, the subservience route means that a government seizes control – whether it be the will of the people or not. This would occur in the context of authoritarian governments. Either way, the government derives its influence from such contexts, thereby deriving its power accordingly.

So what are the key differences between the two? A democratic state would see the government’s power being divided into typically 3 branches – the legislative, executive and judiciary, with the first drafting and passing laws, the second administering the laws and policies, and the third interpreting and upholding them. A simple example of this is the Westminster system in the UK, with parliament, the ministries, and the courts. We will discuss this more in another post.

On the other hand, an authoritarian government would have all its branches typically collapsed into one, or have a farcical separation of powers, which means that on paper, power is separated, but in reality, it is concentrated in the hands of one person or a singular ruling party. They would, in such cases, have the power and influence over all three branches of government. This can come under the utter and total control of one person like in North Korea, or a committee like in China. Different contexts have different structures and as a result some nuances between them, so if you’re interested, drop us a line and ask questions or go read up more on your own. Either way, these structures provide the government with the influence.

As a side note, you may then ask, what about kings? Well, in the past, these seats of power have absolute control, and power is vested in the individual. How the individual comes to power often stems from some form of conquest of territories, and thereafter establishing their rule through claiming divine mandate. Chinese emperors had the Mandate of Heaven, Southeast Asian kingdoms had the Devaraja which was the concept of a god king, and of course, the most famous institution, the British monarchy, used to derive their legitimacy through the Divine Right of Kings, whereby they answer to no authority except God, at least until the Enlightenment. There are modern monarchies, but many of them are constitutional monarchies, except for a select few like Saudi Arabia. But long story short? Monarchies are authoritarian structures.

Regardless of the political structure, as a result of this influence, the government would then have access to the resources and institutions that were established by their predecessors to carry out the act of governance. In cases of a newly independent state, or a less developed one, or a change of regime, they would then have to establish the necessary institutions and processes that would provide them with these resources. That’s where we begin delving into economic policy or the drafting of bodies of laws, but that’s for another day.

Where things go wrong: What is governance

Now, for the last question: where did things go wrong? For governance, the basic way to think about this is as such:

If a government is meant to take care of the people’s interests, why are there cases of them not doing so?

In essence, we want to investigate why things turned out AGAINST the interests of the people. Typically, we do this by asking a few clarification questions and then investigating the causes and impacts of these problems. Broadly speaking, this can be distilled into two things: do people demand things that run contrary to their own interests that cause the governments to go wrong? Or is it a case of just, well, bad governance?

Often, these two things are correlated, especially in democratic contexts. If people demand things of their own representatives in government, their representatives are compelled to bring up such things in the legislative branch, since they are voted into office. If they don’t carry out the will of the people, they risk getting voted out of office. On the other hand, this isn’t too much of a problem in authoritarian contexts, since the government does not necessarily need to wholly represent their people. These are critical questions that you’d have to ask if you want to improve upon your A Levels GP essays or AQs when you are explaining your points.

However, as a side note, in our pursuit of answers to what is governance, we have to recognise that in carrying out the will of the people, we must be cautious about one thing, which is that different viewpoints will inevitably arise in terms of what is considered best for the people. In such scenarios, one may disagree on how those interests can be best served. Such disagreements occur in various contexts, be it in tax reform, education policies, foreign policy, etc., etc.

For example, we may (and we should!) advocate for the mega rich to pay more taxes in order to increase tax revenues to fund government programmes. However, the mega rich will obviously oppose this, since they obviously don’t want to pay more taxes. They may use arguments like, “I worked hard for it,” blah blah blah, and in some cases, maybe. However, that does not bring in the context of how they got there, but we’ll deal with this in another post.

On the other hand, we may advocate for greater spending on support packages to alleviate the costs of the middle-class in society, but economists may oppose this as they may assert that this would not deal with the root of the issue and instead worsen inflation. And indeed that may be the case, if governments don’t deal with wages nor possible price-jacking by big corporations in response to the short-term boosts in consumers’ ability to spend.

Regardless, when investigating how things go wrong, one must first be anchored by the facts underpinning the debates. This means that debates can be had, but only if we agree on some baseline facts. For example, you may have a debate with someone over whether the best ways to deal with, say, increasing obesity rates. You can debate over the merits of approaches like advocacy for more exercise, or regulating food suppliers, health information on products, etc.

But a debate can’t be had if the two opposing sides don’t even accept a common baseline of facts. Maybe one is saying that obesity rates are increasing, but the other one says people are just becoming big-boned. What is there to debate then in that scenario?

If facts are neglected, we risk going down the rabbit hole of dogma or worse, stupidity, as defined by Dietrich Bonhoeffer. We cannot simply choose to believe facts that may conform with our worldviews and we must be more open-minded in accepting different viewpoints, but facts must remain steadfast. Malleable facts are no longer facts, and non-factual debate risks ever-shifting goalposts with the inevitable result of a lack of resolution.

What is Governance – Divining the reasons for its failure

Assuming that a common baseline of facts and concepts is established, we can begin Investigating the reasons for the failure of governance by asking questions on any issues that a nation faces. Such questions can be easily achieved by asking:

- What happened? (Clarification of facts)

- What are the impacts? (Self-explanatory, but this builds on the previous question)

- Why is it a problem? (Again, building on the previous bit)

- How did this happen? (An analysis of the causal factors)

If you’ve seen our case study breakdown of tuition advertising, you’d know that these questions form the backbone of our analysis.

The first three questions require a lot of leg work, assuming you are building your knowledge from the ground up. You need details and facts, so that means copious amounts of research. Intimate knowledge, for better or for worse, is a prerequisite before you can ask the important questions.

That said, the last question is the crucial bit, since various explanations can be produced using various perspectives. In this case, there can be an almost non-exhaustive list of ancillary questions we can ask, like:

- Is there a lack of information that may hamstring a government from taking action?

- Are there sufficient resources AND processes / infrastructure (both tangible and non tangible) to deal with the problem?

- Is there a cultural imperative in society that keeps the government’s hands tied?

- What are the glaring and impactful flaws in the system?

Or, if we really want to investigate possible insidious reasons:

- Are there influences on the government that may detract from the government’s fundamental purpose?

- Is the system inherently favouring certain interests over others?

- Or, you know, is the administration just utterly and irrevocably incompetent and clueless?

Well, these are just some simple questions we can ask ourselves. We will apply these to a case study breakdown in a follow-up post to this post.

Conclusion – What is Governance

Well, in a nutshell, this is the basic framework of governance. To summarise again, the questions we looked at are

- What is governance? It is the act of governing, typically done through laws and policies.

- What is its purpose? Governments have to take care of the short and long term interests of the people.

- How does it derive its purpose? In the modern age, that’s typically done through democratic processes, or through the seizure of power and the subsequent establishment of an authoritarian system.

These are the basics of governance. As we investigate where things go wrong, we will cover more case studies, so keep a lookout for it!

If you’ve found this useful, I strive to offer consumer-friendly A Levels GP and H2 History lessons that are focused on you learning concepts well and of course, applying them in exams. After all, if you can’t apply on your own, it’ll be futile. But we’re much more focused on the former and the process of finding answers (with the given answers, of course) rather than acting as a magic bullet. So if you’re interested, contact us for a free trial lesson!

Contact

9 King Albert Park, KAP Mall, #02-11, S598332

changci@thediscourseeducation.com.sg

9435 2009