General Paper Application Questions (GP AQ) is something that may come as a bit of a jump in rigour for new students. Regardless of whether you are in JC1 or JC2, the A Level GP AQ persistently acts as a thorn on the side of students given that the points can seemingly come out of nowhere arbitrarily. (Spoilers: They don’t.)

Just to contextualise some things, the GP AQ requires students to do a few things: comprehend the given passages, extricate the main argumentative point(s) or theses from the texts, and apply it/them to Singapore’s context. Essentially, they have to assess the author’s/authors’ arguments and make a judgment on whether their arguments hold water.

Common struggles of students include having sufficient knowledge of the Singaporean society, organising and writing their thoughts and arguments, and having the right examples for their arguments. In light of these requirements, naturally, the argument will have to be built upon a strong, foundational understanding of the Singaporean society and its characteristics.

Of course, given the non-exhaustive list of Singapore’s characteristics, it would not make much sense to flesh all of them out in the context of one article. To that end, this article is meant to flesh out one key characteristic of the Singaporean society, which is multiculturalism.

For its basic meaning, multiculturalism refers to the presence and support of multiple distinct ethnicities and cultures within a society. An example of such a characteristic would be New Zealand, where they have a mix of Māori people, Asians, Samoans, European-descended New Zealanders, etc.

Within academia, multiculturalism can have very specific, contextual meanings. In political theory, for instance, it refers to a government’s ability to make use of myriad policies and/or ideologies to effectively manage the presence of multiple ethnicities in their country.

In the context of Singapore, multiculturalism also possesses a couple of different meanings, the first of which is the dictionary meaning of the word. There are multiple ethnicities in Singapore’s society, of whom are supported in one sense or another by the government. (Of course, the extent of said support is not divided along racial lines, but along the lines of nationality.)

To understand how Singapore came to be known as a multicultural society, we need to delve a little bit into its history and the history of the region.

While Southeast Asia has had a highly interesting and in-depth history vis-à-vis the development of cultures and migration, for the current context of Singapore, it suffices to learn about the effects of colonisation on the demographics of this island.

When the British colonised Singapore in 1819, Singapore was developed into a port city in order to capitalise on its advantageous geographical location in serving the trade routes linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Furthermore, it served as one of the Crown Colonies and ports of export for the naturally-occurring tin resources (and over time, rubber and palm oil) in the then-Malaya.

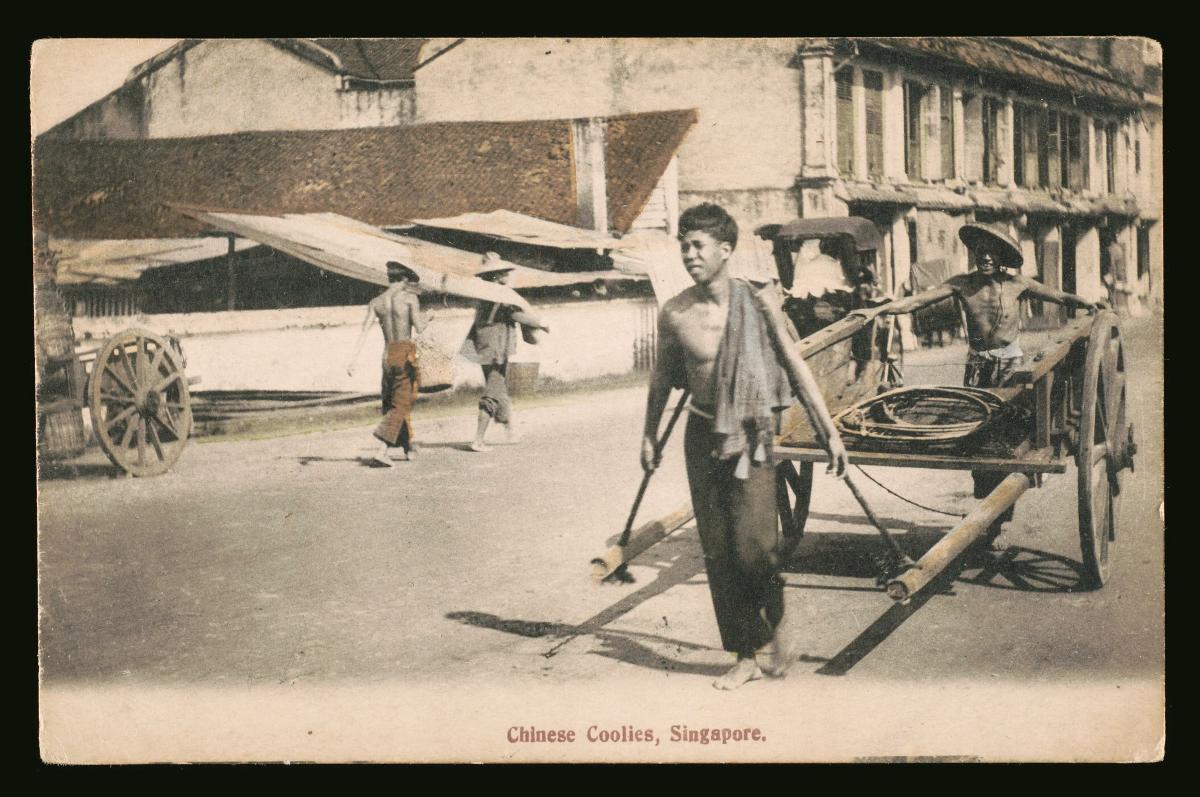

Such a development thus saw the rise of economic opportunities that attracted a variety of fortune-seekers, be they merchants, moneylenders, or even labourers. One of the most-taught example of this is the Chinese coolie, who often worked in harsh conditions, served as indentured labour, and mostly surviving virtually on a subsistence of rice and tea. Other immigrants included Indians (then mostly hailing from the region of Tamil Nadu).

As such, upon independence, Singapore faced the challenge of having to build a nation while dealing with ethnic plurality in the form of the presence of Chinese and Indian immigrants living side-by-side with the local Malays.

This is where things get a little more complicated.

There are a few different end goals of multiculturalism, the most prominent of which would be the idea of a “melting pot” of cultures. To put it simply, it refers to the mixing of the different cultures through cultural exchanges, interracial marriages, etc., to create a single, unitary, homogenous cultural blend.

However, in the case of Singapore, we instead opt for something else, which is a form of multiculturalism akin to a “cultural mosaic”, or more colloquially termed as a “salad bowl” of cultures. This, in short, refers to the coexistence of different ethnicities, cultures and religions within a society.

Such coexistence, in addition, assumes that these different communities are living harmoniously with one another and working towards the common good of society, rather than a simple side-by-side coexistence without any actual interactions between them. This is taken further with an overt emphasis on the maintenance of communities’ individual cultural heritage and roots.

Indeed, as asserted by DPM Lawrence Wong in a keynote speech in 2021 during a forum on race relations and racism jointly organised by the Institute of Policy Studies and the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, that is the Singapore government’s philosophy on multiculturalism.

“We did not set out to achieve racial harmony by creating a monolithic society. Our multiracialism does not require any community to give up its heritage or traditions. Ours is not the French way, insisting on assimilation into one master language and culture. Instead, we decided to preserve, protect and celebrate our diversity; hence, we encourage each community to take pride in its own cultures and traditions. At the same time, we seek common ground among our communities and aim to expand our common space [sic] and strengthen our shared sense of belonging and identity.”

Lawrence Wong

Suffice to say, this approach has been entrenched in our policy-making ever since independence; barring any unforeseen circumstances like, say, a meteorite hitting Earth, this would presumably continue for the rest of PAP’s rule in power, however long it may turn out to be.

As a result of being a multicultural nation, Singapore has to constantly keep at the fore of its policies the consideration of potential fault lines between the different ethnicities living in this country. As much as Singapore has come a long way from the early 20th century that was plagued with race riots and racial tension, cultural differences continue to exist.

Compound to this a somewhat open immigration policy, such differences will deepen even further with incoming immigrations that bring with them yet more cultures. Such differences can manifest in cases like Tan Boon Lee who accosted an interracial couple, or a fiery Preetipls response to the head-scratching decision of rolling out the Brownface Ad in 2019.

These are just the highly prominent cases; we still have yet to explore the smaller disputes that may exist in tabloids or, worse, racist behaviour that do not get the negative attention that it should.

Therefore, a careful and measured approach is necessary on the part of the government in order to ensure the continued harmony between the different communities, while being mindful that such peace can never be taken for granted and must always be assumed to be tenuous at best.

This, of course, in no way suggests that the Singapore society automatically assumes conflict between the different communities; it actively takes measures – be it on the government’s part or on the citizens’ part – to build bridges between the different ethnicities.

If we were to anthropomorphise Singapore, its characteristics in turn drive the behaviours of the people in the society. In addition, it also sets the context for what can or cannot be allowed in Singapore.

For instance, if we have passages that assert the idea of the necessity of having a melting pot of cultures in the context of USA, such an idea cannot be applied to Singapore in the GP AQ. If we have passages that posit the significance of clothing on our cultural identity, this can indeed be applied to Singapore in the GP AQ, given the myriad clothing designs that are unique to each cultures in this nation.

Of course, to delve into this on a deeper level, especially in relation to how the writing will turn out, this will be reserved for another post, our A Level GP Tuition lessons, or you can contact us by dropping a Whatsapp message to clarify, or book us for a free consultation for the GP AQ.

Given that multiculturalism is so ingrained in the Singapore society, it forms one of the keystones in the construction of a national and cultural identity. Consequently, such significance lends itself to the adoption of various possible lenses to analyse this cultural aspect of Singapore vis-à-vis other characteristics in the nation, such as politics, education, economics, etc.

It bleeds into and influences every aspect of our lives in Singapore. If not for the A Level GP AQ, at the very least it serves as a crucial framework to understand the machinations of and what drives policy-making in our society.

Why do we need to understand Singapore’s Characteristics?

Featured Image by Zhu Hongzhi on Unsplash